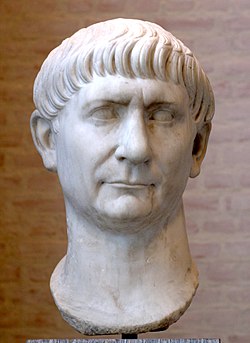

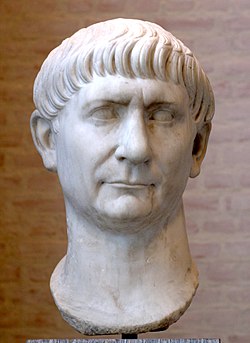

Trajan -Roman Emperor : 98-117 A.D. -

Silver Denarius 18mm (3.39 grams) Struck circa 101-102 A.D.

Reference: RIC 56b; Cohen 238. (RIC describes the coin as Felicitas with the attributes

of Pax, as on RIC 6)

IMP CAES NERVA TRAIAN AVG GERM, laureate head right

P M TR P COS IIII P P, Felicitas or Pax standing left, holding branch & cornucopia. You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity. Eirene, or Irene Greek for "peace"; theRoman equivalent wasPax, one of theHorae, was the personification of peace, and was depicted in art as a beautiful young woman carrying acornucopia,sceptre and a torch orrhyton. She is said sometimes to be the daughter of Zeus andThemis. She was particularly well regarded by thecitizens of Athens. After a naval victory overSparta in 375 BC, the Athenians established a cult for Eirene, erectingaltars to her. They held an annual state sacrifice to her after 371 BC to commemorate theCommon Peace of that year and set up a votive statue in her honour in theAgora of Athens. The statue was executed in bronze byCephisodotus the Elder, likely the father or uncle of the famous sculptorPraxiteles. It was acclaimed by the Athenians, who depicted it on vases and coins. Although the statue is now lost, it was copied in marble by the Romans; one of the best surviving copies (right) is in theMunichGlyptothek. It depicts the goddess carrying a child with her left arm –Ploutos, the god of plenty and son ofDemeter, the goddess of agriculture. Eirenes missing right hand once held a sceptre. She is shown gazing maternally at Ploutos, who is looking back at her trustingly. The statue is an allegory for Plenty (Ploutos) prospering under the protection of Peace (Eirene); it constituted a public appeal to good sense. The copy in the Glyptothek was originally in the collection of theVilla Albani in Rome but was looted and taken to France by Napoleon I. Following Napoleons fall, the statue was bought byLudwig I of Bavaria.  In Roman mythology, Pax (Latin for peace) (herGreek equivalent was Eirene) was recognized as agoddess during the rule ofAugustus. On theCampus Martius, she had a temple called theAra Pacis, and another temple on theForum Pacis. She was depicted in art witholive branches, acornucopia and a scepter. There was a festival in her honor on January 3. Daughter ofJupiter andIustitia. Pax was often associated with spring. In Roman mythology, Pax (Latin for peace) (herGreek equivalent was Eirene) was recognized as agoddess during the rule ofAugustus. On theCampus Martius, she had a temple called theAra Pacis, and another temple on theForum Pacis. She was depicted in art witholive branches, acornucopia and a scepter. There was a festival in her honor on January 3. Daughter ofJupiter andIustitia. Pax was often associated with spring.

Inancient Roman culture, felicitas (from the Latinadjective felix, "fruitful, blessed, happy, lucky") is a condition of divinely inspired productivity, blessedness, orhappiness. Felicitas could encompass both a womans fertility, and a generals luck or good fortune. The divine personification of Felicitas wascultivated as a goddess. Although felicitas may be translated as "good luck," and the goddess Felicitas shares some characteristics and attributes withFortuna, the two were distinguished inRoman religion.Fortuna was unpredictable and her effects could be negative, as the existence of an altar to Mala Fortuna ("Bad Luck") acknowledges.Felicitas, however, always had a positive significance. She appears withseveral epithets that focus on aspects of her divine power. Felicitas had a temple in Rome as early as the mid-2nd century BC, and during the Republican eraa was honored at twoofficial festivals ofRoman state religion, on July 1 in conjunction withJuno and October 9 as Fausta Felicitas. Felicitas continued to play an important role inImperial cult, and was frequently portrayed oncoins as a symbol of the wealth and prosperity of the Roman Empire. Her primary attributes are thecaduceus andcornucopia.The English word "felicity" derives from felicitas. As virtue or quality  Phallic relief with the inscription "Felicitas dwells here" In its religious sense, felix means "blessed, under the protection or favour of the gods; happy." That which is felix has achieved the pax divom, a state of harmony or peace with the divine world. The word derives fromIndo-European *dhe(i)l, meaning "happy, fruitful, productive, full of nourishment." Related Latin words include femina, "woman" (a person who provides nourishment or suckles); felo, "to suckle" in regard to an infant; filius, "son" (a person suckled); and probably fello, fellare, "to performfellatio", with an originally non-sexual meaning of "to suck". The continued magical association of sexual potency, increase, and general good fortune in productivity is indicated by the inscription Hic habitat Felicitas ("Felicitas dwells here")[8] on anapotropaic relief of a phallus at a bakery inPompeii. In archaic Roman culture, felicitas was a quality expressing the close bonds betweenreligion and agriculture. Felicitas was at issue when the suovetaurilia sacrifice conducted byCato the Elder ascensor in 184 BC was challenged as having been unproductive, perhaps for vitium, ritual error. In the following three years Rome had been plagued by a number of ill omens and prodigies (prodigia), such as severe storms, pestilence, and "showers of blood," which had required a series of expiations (supplicationes). The speech Cato gave to justify himself is known as the Oratio de lustri sui felicitate, "Speech on the Felicitas of hisLustrum", and survives only as a possible quotation by a later source. Cato says that a lustrum should be found to have produced felicitas "if the crops had filled up the storehouses, if the vintage had been abundant, if the olive oil had flowed deliberately from the groves", regardless of whatever else might have occurred. The efficacy of a ritual might be thus expressed as its felicitas. The ability to promote felicitas became proof of ones excellence and divine favor. Felicitas was simultaneously a divine gift, a quality that resided within an individual, and a contagious capacity for generating productive conditions outside oneself: it was a form of "charismatic authority". Cicero lists felicitas as one of the four virtues of the exemplary general, along with knowledge ofmilitary science (scientia rei militaris),virtus (both "valor" and "virtue"), and auctoritas, "authority." Virtus was a regular complement to felicitas, which was not thought to attach to those who were unworthy. Cicero attributed felicitas particularly toPompeius Magnus ("Pompey the Great"), and distinguished this felicitas even from the divine good luck enjoyed by successful generals such asFabius Maximus, Marcellus,Scipio the Younger andMarius. The sayings (sententiae) ofPublilius Syrus are often attached to divine qualities, including Felicitas: "The peoples Felicitas is powerful when she is merciful" (potens misericors publica est Felicitas). Epithets Epithets of Felicitas include: - Augusta , the goddess in her association with the emperor and Imperial cult .

- Fausta ("Favored, Fortunate"), a state divinity cultivated on October 9 in conjunction with Venus Victrix and the Genius Populi Romani ("Genius" of the Roman People, also known as the Genius Publicus).

- Publica, the "public" Felicitas; that is, the aspect of the divine force that was concerned with the res publica or commonwealth, or with the Roman People (Populus Romanus).

- Temporum, the Felicitas "of the times", a title which emphasize the felicitas being experienced in current circumstances.

Republic Thecult of Felicitas is first recorded in the mid-2nd century BC, when atemple was dedicated to her byLucius Licinius Lucullus, grandfather of the famous Lucullus, using booty from his military campaigns inSpain in 151–150 BC. Predecessor to a noted connoisseur of art, Lucullus obtained and dedicated several statues looted byMummius fromGreece, including works byPraxiteles: the Thespiades, a statue group of theMuses brought fromThespiae, and aVenus. This Temple of Felicitas was among several that had a secondary function as art museums, and was recommended byCicero along with theFortuna Huiusce DieiTemple of for those who enjoyed viewing art but lacked the means to amass private collections. The temple was located in theVelabrum in the Vicus Tuscus of theCampus Martius, along a route associated withtriumphs: the axle ofJulius Caesars triumphalchariot in 46 BC is supposed to have broken in front of it. The temple was destroyed by a fire during the reign ofClaudius, though the Muses were rescued. It was not rebuilt at this site. Sulla identified himself so closely with the quality of felicitcas that he adopted the agnomen (nickname) Felix. His domination asdictator resulted from civil war and unprecedented military violence within the city of Rome itself, but he legitimated his authority by claiming that the mere fact of his victory was proof he was felix and enjoyed the divine favor of the gods. Republican precedent was to regard a victory as belonging to the Roman people as a whole, as represented by thetriumphal procession at which the honored general submitted public offerings at theTemple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus at theCapitol, and Sulla thus established an important theological element for the later authority of the emperor. Although he established no new temple for Felicitas, he celebrated games (ludi circenses) in her honor. On July 1 and October 9, Felicitas received a sacrifice in Capitolio, on theCapitoline Hill, on the latter date as Fausta Felicitas in conjunction with the Genius Publicus ("PublicGenius") andVenus Victrix. These observances probably took place at an altar or small shrine (aedicula), not a separatetemple precinct. TheActs of the Arval Brothers (1st century AD) prescribe a cow as the sacrifice for Felicitas. Pompey established a shrine for Felicitas athis new theater and temple complex, which used the steps to the Temple of Venus Victrix as seating. Felicitas was cultivated with Honor and Virtue, and she may have shared her shrine there withVictory, as she did in the Imperial era as Felicitas Caesaris (Caesars Felicitas) atAmeria. Pompeys collocation of deities may have been intended to parallel the Capitoline grouping. A fourth cult site for Felicitas in Rome had been planned by Caesar, and possibly begun before his death. Work on the temple was finished byLepidus on the site of theCuria Hostilia, which had been restored by Sulla, destroyed by fire in 52 BC, and demolished by Caesar in 44 BC. This temple seems not to have existed by the time ofHadrian. Its site probably lies under the church ofSanti Luca e Martina. v It has been suggested that anIonic capital and atufa wall uncovered at the site are the only known remains of the temple. Felicitas was awatchword used by Julius Caesars troops at theBattle of Thapsus, the names of deities and divine personifications being often recorded for this purpose in the late Republic. Felicitas Iulia ("Julian Felicitas") was the name of acolony inRoman Spain that was refounded under Caesar and known also as Olisipo, present-day Lisbon, Portugal. During the Republic, only divine personifications known to have had a temple or public altar were featured on coins, among them Felicitas. On the only extant Republican coin type, Felicitas appears as a bust and wearing adiadem. Empire  Felicitas Temporum represented by a pair of cornucopiae on a denarius (193-194 AD) issued under Pescennius Niger A calendar from Cumae records that a supplicatio was celebrated on April 16 for the Felicitas of the Empire, in honor of the dayAugustus was first acclaimed imperator. In extant Roman coinage, Felicitas appears with acaduceus only during the Imperial period. The earliest known example is Felicitas Publica on a dupondius issued underGalba. Felicitas Temporum ("Prosperity of the Times"), reflecting aGolden Age ideology, was among the innovative virtues that began to appear during the reigns ofTrajan andAntoninus Pius.Septimius Severus, whose reign followed the exceedingly brief tenure ofPertinax and unsatisfactory conditions underCommodus, used coinage to express his efforts toward restoring thePax Romana, with themes such as Felicitas Temporum and Felicitas Saeculi, "Prosperity of the Age" (saeculum), prevalent in the years 200 to 202. Some Imperial coins use these phrases with images of women and children in the emperors family. When the Empire came under Christian rule, the personified virtues that had been cultivated as deities could be treated as abstract concepts. Felicitas Perpetua Saeculi ("Perpetual Blessedness of the Age") appears on a coin issued underConstantine, the first emperor to convert to Christianity. The cornucopia (from Latin cornu copiae) or horn of plenty is a symbol of abundance and nourishment, commonly a large horn-shaped container overflowing with produce, flowers, nuts, other edibles, or wealth in some form. Originating inclassical antiquity, it has continued as a symbol inWestern art, and it is particularly associated with theThanksgiving holiday inNorth America.  Allegorical depiction of the Roman goddess Abundantia with a cornucopia, by Rubens (ca. 1630) In MythologyMythology offers multipleexplanations of the origin of the cornucopia. One of the best-known involves the birth and nurturance of the infantZeus, who had to be hidden from his devouring fatherCronus. In a cave onMount Ida on the island ofCrete, baby Zeus was cared for and protected by a number of divine attendants, including the goatAmalthea ("Nourishing Goddess"), who fed him with her milk. The suckling future king of the gods had unusual abilities and strength, and in playing with his nursemaid accidentally broke off one of herhorns, which then had the divine power to provide unending nourishment, as the foster mother had to the god. In another myth, the cornucopia was created whenHeracles (RomanHercules) wrestled with the river godAchelous and wrenched off one of his horns; river gods were sometimes depicted as horned. This version is represented in theAchelous and Herculesmural painting by theAmerican Regionalist artistThomas Hart Benton. The cornucopia became the attribute of severalGreek andRoman deities, particularly those associated with the harvest, prosperity, or spiritual abundance, such as personifications of Earth (Gaia orTerra); the childPlutus, god of riches and son of the grain goddess Demeter; thenymphMaia; andFortuna, the goddess of luck, who had the power to grant prosperity. InRoman Imperial cult, abstract Roman deities who fostered peace (pax Romana) and prosperity were also depicted with a cornucopia, including Abundantia, "Abundance" personified, andAnnona, goddess of thegrain supply to the city of Rome.Pluto, the classical ruler of the underworld in themystery religions, was a giver of agricultural, mineral and spiritual wealth, and in art often holds a cornucopia to distinguish him from the gloomier Hades, who holds adrinking horn instead. Modern depictionsIn modern depictions, the cornucopia is typically a hollow, horn-shaped wicker basket filled with various kinds of festivefruit andvegetables. In North America, the cornucopia has come to be associated withThanksgiving and the harvest. Cornucopia is also the name of the annual November Wine and Food celebration inWhistler, British Columbia, Canada. Two cornucopias are seen in theflag andstate seal ofIdaho. The GreatSeal ofNorth Carolina depicts Liberty standing and Plenty holding a cornucopia. The coat of arms ofColombia,Panama,Peru andVenezuela, and the Coat of Arms of the State ofVictoria, Australia, also feature the cornucopia, symbolising prosperity. The horn of plenty is used on body art and at Halloween, as it is a symbol of fertility, fortune and abundance. -

Base of a statue of

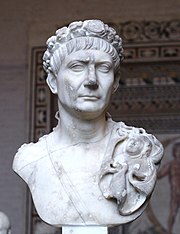

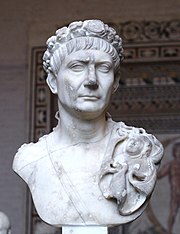

Louis XV of France Marcus Ulpius Nerva Traianus, commonly known as Trajan (18 September, 53 – 8 August, 117), was a Roman Emperor who reigned from AD 98 until his death in AD 117. Born Marcus Ulpius Traianus into a non-patrician family in theHispania Baetica province (modern daySpain), Trajan rose to prominence during the reign of emperorDomitian, serving as a general in theRoman army along theGerman frontier, and successfully crushing the revolt ofAntonius Saturninus in 89. On September 18, 96, Domitian was succeeded byMarcus Cocceius Nerva, an old and childless senator who proved to be unpopular with the army. After a brief and tumultuous year in power, a revolt by members of thePraetorian Guard compelled him to adopt the more popular Trajan as his heir and successor. Nerva died on January 27, 98, and was succeeded by his adopted son without incident. Roman Emperor who reigned from AD 98 until his death in AD 117. Born Marcus Ulpius Traianus into a non-patrician family in theHispania Baetica province (modern daySpain), Trajan rose to prominence during the reign of emperorDomitian, serving as a general in theRoman army along theGerman frontier, and successfully crushing the revolt ofAntonius Saturninus in 89. On September 18, 96, Domitian was succeeded byMarcus Cocceius Nerva, an old and childless senator who proved to be unpopular with the army. After a brief and tumultuous year in power, a revolt by members of thePraetorian Guard compelled him to adopt the more popular Trajan as his heir and successor. Nerva died on January 27, 98, and was succeeded by his adopted son without incident. As a civilian administrator, Trajan is best known for his extensive public building program, which reshaped the city of Rome and left multiple enduring landmarks such asTrajans Forum,Trajans Market andTrajans Column. It was as a military commander however that Trajan celebrated his greatesttriumphs. In 101, he launched apunitive expedition into the kingdom ofDacia against kingDecebalus, defeating the Dacian army nearTapae in 102, and finally conquering Dacia completely in 106. In 107, Trajan pushed further east and annexed theNabataean kingdom, establishing the province ofArabia Petraea. After a period of relative peace within the Empire, he launched his final campaign in 113 againstParthia, advancing as far as the city ofSusa in 116, and expanding the Roman Empire to its greatest extent. During this campaign Trajan was struck by illness, and late in 117, while sailing back to Rome, he died of astroke onAugust 9, in the city ofSelinus. He wasdeified by the Senate and his ashes were laid to rest underTrajans Column. He was succeeded by his adopted son (not having a biological heir)Publius Aelius Hadrianus—commonly known as Hadrian. As an emperor, Trajans reputation has endured - he is one of the few rulers whose reputation has survived the scrutiny of nineteen centuries of history. Every new emperor after him was honoured by the Senate with the prayer felicior Augusto, melior Traiano, meaning "may he be luckier thanAugustus and better than Trajan". Amongmedieval Christian theologians, Trajan was considered avirtuous pagan, while the 18th century historianEdward Gibbon popularized the notion of theFive Good Emperors, of which Trajan was the second. Early life and rise to powerTrajan was born on September 18, 53 in the Roman province ofHispania Baetica (in what is nowAndalusia in modern Spain), a province that was thoroughly Romanized and called southern Hispania, in the city ofItalica, where theItalian families were paramount. OfItalian stock himself, Trajan is frequently but misleadingly designated the first provincial emperor. Trajan was the son ofMarcia andMarcus Ulpius Traianus, a prominentsenator and general from the famous Ulpiagens. Trajan himself was just one of many well-known Ulpii in a line that continued long after his own death. His elder sister wasUlpia Marciana and his niece wasSalonina Matidia. The patria of the Ulpii wasItalica, in Spanish Baetica, where their ancestors had settled late in the third century B.C. This indicates that the Italian origin was paramount, yet it has recently been cogently argued that the familys ancestry was local, with Trajan senior actually a Traius who was adopted into the family of the Ulpii. As a young man, he rose through the ranks of theRoman army, serving in some of the most contentious parts of the Empires frontier. In 76–77, Trajans father wasGovernor ofSyria (Legatus pro praetore Syriae), where Trajan himself remained as Tribunus legionis. Trajan was nominated asConsul and broughtApollodorus of Damascus with him toRome around 91. Along theRhine River, he took part in the EmperorDomitians wars while under Domitians successor, Nerva, who was unpopular with the army and needed to do something to gain their support. He accomplished this by naming Trajan as his adoptive son and successor in the summer of 97. According to theAugustan History, it was the future EmperorHadrian who brought word to Trajan of his adoption. When Nerva died on January 27, 98, the highly respected Trajan succeeded without incident. His reignThe new Roman emperor was greeted by the people of Rome with great enthusiasm, which he justified by governing well and without the bloodiness that had marked Domitians reign. He freed many people who had been unjustly imprisoned by Domitian and returned a great deal of private property that Domitian had confiscated; a process begun by Nerva before his death. His popularity was such that theRoman Senate eventually bestowed upon Trajan the honorific of optimus, meaning "the best". Dio Cassius, sometimes known as Dio, reveals that Trajan drank heartily and wasinvolved with boys. "I know, of course, that he was devoted to boys and to wine, but if he had ever committed or endured any base or wicked deed as the result of this, he would have incurred censure; as it was, however, he drank all the wine he wanted, yet remained sober, and in his relation with boys he harmed no one." This sensibility was one that influenced his governing on at least one occasion, leading him to favour the king of Edessa out of appreciation for his handsome son: "On this occasion, however,Abgarus, induced partly by the persuasions of his son Arbandes, who was handsome and in the pride of youth and therefore in favour with Trajan, and partly by his fear of the latters presence, he met him on the road, made his apologies and obtained pardon, for he had a powerful intercessor in the boy." Dacian WarsIt was as a military commander that Trajan is best known to history, particularly for his conquests in theNear East, but initially for the two wars against Dacia — the reduction to client kingdom (101-102), followed by actual incorporation to the Empire of the trans-Danube border kingdom of Dacia—an area that had troubled Roman thought for over a decade with the unfavourable (and to some, shameful) peace negotiated byDomitians ministers In the first war c. March–May 101, he launched a vicious attack into the kingdom ofDacia with four legions, crossing to the northern bank of theDanube River on a stone bridge he had built, and defeating the Dacian army near or in amountain pass calledTapae (seeSecond Battle of Tapae). Trajans troops were mauled in the encounter, however and he put off further campaigning for the year to heal troops, reinforce, and regroup. During the following winter, KingDecebalus launched a counter-attack across theDanube further downstream, but this was repulsed. Trajans army advanced further into Dacian territory and forced King Decebalus to submit to him a year later, after Trajan took the Dacian capital/fortress ofSarmizegethusa. The Emperor Domitian had campaigned againstDacia from 86 to 87 without securing a decisive outcome, and Decebalus had brazenly flouted the terms of the peace (89 AD) which had been agreed on conclusion of this campaign. Trajan now returned to Rome in triumph and was granted the title Dacicus Maximus. The victory was celebrated by theTropaeum Traiani. Decebalus though, after being left to his own devices, in 105 undertook an invasion against Roman territory by attempting to stir up some of the tribes north of the river against her. Trajan took to the field again and after building with the design of Apollodorus of Damascus hismassive bridge over the Danube, he conquered Dacia completely in 106. Sarmizegethusa was destroyed,Decebalus committedsuicide, and his severed head was exhibited in Rome on the steps leading up to theCapitol. Trajan built a new city, "Colonia Ulpia Traiana Augusta Dacica Sarmizegetusa", on another site than the previous Dacian Capital, although bearing the same full name, Sarmizegetusa. He resettled Dacia with Romans and annexed it as a province of the Roman Empire. Trajans Dacian campaigns benefited the Empires finances through the acquisition of Dacias gold mines. The victory is celebrated byTrajans Column. Expansion in the EastAt about the same timeRabbel II Soter, one of Romes client kings, died. This event might have prompted the annexation of theNabataean kingdom, although the manner and the formal reasons for the annexation are unclear. Some epigraphic evidence suggests a military operation, with forces fromSyria andEgypt. What is clear, however, is that by 107, Roman legions were stationed in the area aroundPetra andBostra, as is shown by a papyrus found in Egypt. The empire gained what became the province ofArabia Petraea (modern southernJordan and north westSaudi Arabia). Period of peaceThe next seven years, Trajan ruled as a civilian emperor, to the same acclaim as before. It was during this time that he corresponded withPliny the Younger on the subject of how to deal with theChristians ofPontus, telling Pliny to leave them alone unless they were openly practicing the religion. He built several new buildings, monuments and roads inItalia and his nativeHispania. His magnificent complex in Rome raised to commemorate his victories inDacia (and largely financed from that campaigns loot)—consisting of aforum,Trajans Column, and Trajans Market still stands in Rome today. He was alsoa prolific builder of triumphal arches, many of which survive, and rebuilder of roads (Via Traiana andVia Traiana Nova). One notable act of Trajan was the hosting of a three-monthgladiatorial festival in the greatColosseum in Rome (the precise date of this festival is unknown). Combining chariot racing, beast fights and close-quarters gladiatorial bloodshed, this gory spectacle reputedly left 11,000 dead (mostly slaves and criminals, not to mention the thousands of ferocious beasts killed alongside them) and attracted a total of five million spectators over the course of the festival. Another important act was his formalisation of the Alimenta, a welfare program that helped orphans and poor children throughout Italy. It provided general funds, as well as food and subsidized education. The program was supported initially by funds from the Dacian War, and then later by a combination of estate taxes and philanthropy.[13]. Although the system is well documented in literary sources and contemporary epigraphy, its precise aims are controversial and have generated considerable dispute between modern scholars: usually, its assumed that the programme intended to bolster citzen numbers in Italy. However, the fact that it was subsidized by means of interest payments on loans made by landowners restricted it to a small percentage of potential welfare recipients (Paul Veyne has assumed that, in the city ofVeleia, only one child out of ten was an actual beneficiary) - therefore, the idea, advanced byMoses I. Finley, that the whole scheme was at most a form of random charity, a mere imperial benevolence[14]. Maximum extent of the Empire  The extent of the Roman Empire under Trajan (117) In 113, he embarked on his last campaign, provoked byParthias decision to put an unacceptable king on the throne of Armenia, a kingdom over which the two great empires had sharedhegemony since the time ofNero some fifty years earlier. Some modern historians also attribute Trajans decision to wage war on Parthia to economic motives: to control, after the annexation of Arabia, Mesopotamia and the coast of the Persian Gulf, and with it the sole remaining receiving-end of the Indian trade outside Roman control - an attribution of motive other historians find absurd, as seeing a commercial motive in a campaign triggered by the lure of territorial annexation and prestige - by the way, the only motive for Trajans actions ascribed by Dio Cassius in his description of the events. Other modern historians, however, think that Trajans original aim was quite modest: to assure a more defensible Eastern frontier for the Roman Empire, crossing across Northern Mesopotamia along the course of the riverKhabur in order to offer cover to a Roman Armenia. Trajan marched first on Armenia, deposed the Parthian-appointed king (who was afterwards murdered while kept in the custody of Roman troops in an unclear incident) and annexed it to the Roman Empire as a province, receiving in passing the acknowledgement of Roman hegemony by various tribes in the Caucasus and on the Eastern coast of the Black Sea - a process that kept him busy until the end of 114]. The cronology of subsequent events is uncertain, but its generally believed that early in 115 Trajan turned south into the core Parthian hegemony, taking the Northern Mesopotamian cities ofNisibis andBatnae and organizing a province ofMesopotamia in the beginning of 116, when coins were issued announcing that Armenia and Mesopotamia had been put under the authority of the Roman people. In early 116, however, Trajan began to toy with the conquest of the whole of Mesopotamia, an overambitious goal that eventually backfired on the results of his entire campaign: One Roman division crossed theTigris intoAdiabene, sweeping South and capturingAdenystrae; a second followed the river South, capturing Babylon; while Trajan himself sailed down theEuphrates, then dragged his fleet overland into the Tigris, capturingSeleucia and finally the Parthian capital ofCtesiphon. He continued southward to thePersian Gulf, receiving the submission of Athambelus, the ruler ofCharax, whence he declared Babylon a new province of the Empire, sent the Senate a laurelled letter declaring the war to be at a close and lamented that he was too old to follow in the steps ofAlexander the Great and reach the distantIndia itself. A province ofAssyria was also proclaimed, apparently covering the territory of Adiabene, as well as some measures seem to have been considered about the fiscal administration of the Indian trade. However, as Trajan left the Persian Gulf for Babylon - where he intended to offer sacrifice to Alexander in the house where he had died in 323 B.C.- a sudden outburst of Parthian resistance, led by a nephew of the Parthian king, Sanatrukes, imperilled Roman positions in Mesopotamia and Armenia, something Trajan sought to deal with by forsaking direct Roman rule in Parthia proper, at least partially: later in 116, after defeating a Parthian army in a battle where Sanatrukes was killed and re-taking Seleucia, he formally deposed the Parthian kingOsroes I and put his own puppet rulerParthamaspates on the throne. That done, he retreated North in order to retain what he could of the new provinces of Armenia and Mesopotamia.  Bust of Trajan, Glyptothek , Munich . It was at this point that Trajans health started to fail him. The fortress city ofHatra, on theTigris in his rear, continued to hold out against repeated Roman assaults. He was personally present at thesiege and it is possible that he suffered a heat stroke while in the blazing heat. Shortly afterwards, theJews inside the Eastern Roman Empire rose up in rebellion once more, as did the people of Mesopotamia. Trajan was forced to withdraw his army in order to put down the revolts. Trajan saw it as simply a temporary setback, but he was destined never to command an army in the field again, turning his Eastern armies over to the high ranking legate and governor of Judaea,Lusius Quietus, who in early 116 had been in charge of the Roman division who had recovered Nisibis andEdessa from the rebels; Quietus was promised for this a consulate in the following year - when he was actually put to death by Hadrian , who had no use for a man so committed to Trajans aggressive policies. Early in 117, Trajan grew ill and set out to sail back to Italy. His health declined throughout the spring and summer of 117, something publicy acknowledged by the fact that a bronze bust displayed at the time in the public baths ofAncyra showed him clearly aged and edemaciated. By the time he had reached Selinus inCilicia which was afterwards called Trajanopolis, he suddenly died fromedema on August 9. Some say that he had adoptedHadrian as his successor, but others that it was his wifePompeia Plotina who hired someone to impersonate him after he had died. Hadrian, upon becoming ruler, recognized the abandonment of Mesopotamia and restored Armenia - as well asOsroene - to the Parthian hegemony under Roman suzerainty - a telling sign the Roman Empire lacked the means for pursuing Trajans overambitious goals. However, all the other territories conquered by Trajan were retained. Trajans ashes were laid to rest underneath Trajans column, the monument commemorating his success.  The Alcántara Bridge , widely hailed as a masterpiece of Roman engineering . Building activitiesTrajan was a prolific builder in Rome and the provinces, and many of his buildings were erected by the gifted architectApollodorus of Damascus. Notable structures includeTrajans Column,Trajans Forum,Trajans Bridge,Alcántara Bridge, and possibly theAlconétar Bridge. In order to build his forum and the adjacent brick market that also held his name Trajan had vast areas of the surrounding hillsides leveled. Trajans legacyUnlike many lauded rulers in history, Trajans reputation has survived undiminished for nearly nineteen centuries. Ancient sources on Trajans personality and accomplishments are unanimously positive. Pliny the younger, for example, celebrates Trajan in his panegyric as a wise and just emperor and a moral man.Dio Cassius admits Trajan had vices like heavy drinking and sexual involvement with boys, but added that he always remained dignified and fair. TheChristianisation of Rome resulted in further embellishment of his legend: it was commonly said inmedieval times thatPope Gregory I, through divine intercession, resurrected Trajan from the dead and baptized him into the Christian faith. An account of this features in theGolden Legend. Theologians, such asThomas Aquinas, discussed Trajan as an example of a virtuous pagan. Inthe Divine Comedy,Dante, following this legend, sees the spirit of Trajan in the Heaven ofJupiter with other historical and mythological persons noted for their justice. He also features in Piers Plowman. An episode, referred to as thejustice of Trajan was reflected in several art works. In the 18th Century KingCharles III of Spain comminsionedAnton Raphael Mengs to paint The Triumph of Trajan on the ceiling of the banqueting-hall of theRoyal Palace of Madrid - considered among the best work of this artist. "Traian" is used as a male first name in present-dayRomania - among others, that of the countrys incumbent president,Traian Băsescu. |

In Roman mythology, Pax (Latin for peace) (herGreek equivalent was Eirene) was recognized as agoddess during the rule ofAugustus. On theCampus Martius, she had a temple called theAra Pacis, and another temple on theForum Pacis. She was depicted in art witholive branches, acornucopia and a scepter. There was a festival in her honor on January 3. Daughter ofJupiter andIustitia. Pax was often associated with spring.

In Roman mythology, Pax (Latin for peace) (herGreek equivalent was Eirene) was recognized as agoddess during the rule ofAugustus. On theCampus Martius, she had a temple called theAra Pacis, and another temple on theForum Pacis. She was depicted in art witholive branches, acornucopia and a scepter. There was a festival in her honor on January 3. Daughter ofJupiter andIustitia. Pax was often associated with spring.

Roman Emperor who reigned from AD 98 until his death in AD 117. Born Marcus Ulpius Traianus into a non-patrician family in theHispania Baetica province (modern daySpain), Trajan rose to prominence during the reign of emperorDomitian, serving as a general in theRoman army along theGerman frontier, and successfully crushing the revolt ofAntonius Saturninus in 89. On September 18, 96, Domitian was succeeded byMarcus Cocceius Nerva, an old and childless senator who proved to be unpopular with the army. After a brief and tumultuous year in power, a revolt by members of thePraetorian Guard compelled him to adopt the more popular Trajan as his heir and successor. Nerva died on January 27, 98, and was succeeded by his adopted son without incident.

Roman Emperor who reigned from AD 98 until his death in AD 117. Born Marcus Ulpius Traianus into a non-patrician family in theHispania Baetica province (modern daySpain), Trajan rose to prominence during the reign of emperorDomitian, serving as a general in theRoman army along theGerman frontier, and successfully crushing the revolt ofAntonius Saturninus in 89. On September 18, 96, Domitian was succeeded byMarcus Cocceius Nerva, an old and childless senator who proved to be unpopular with the army. After a brief and tumultuous year in power, a revolt by members of thePraetorian Guard compelled him to adopt the more popular Trajan as his heir and successor. Nerva died on January 27, 98, and was succeeded by his adopted son without incident.